Training Large Language Models with Curriculum Learning (2020-2025)

By Dr. Mike Erlihson and Dr. Barak Or

Introduction and Background

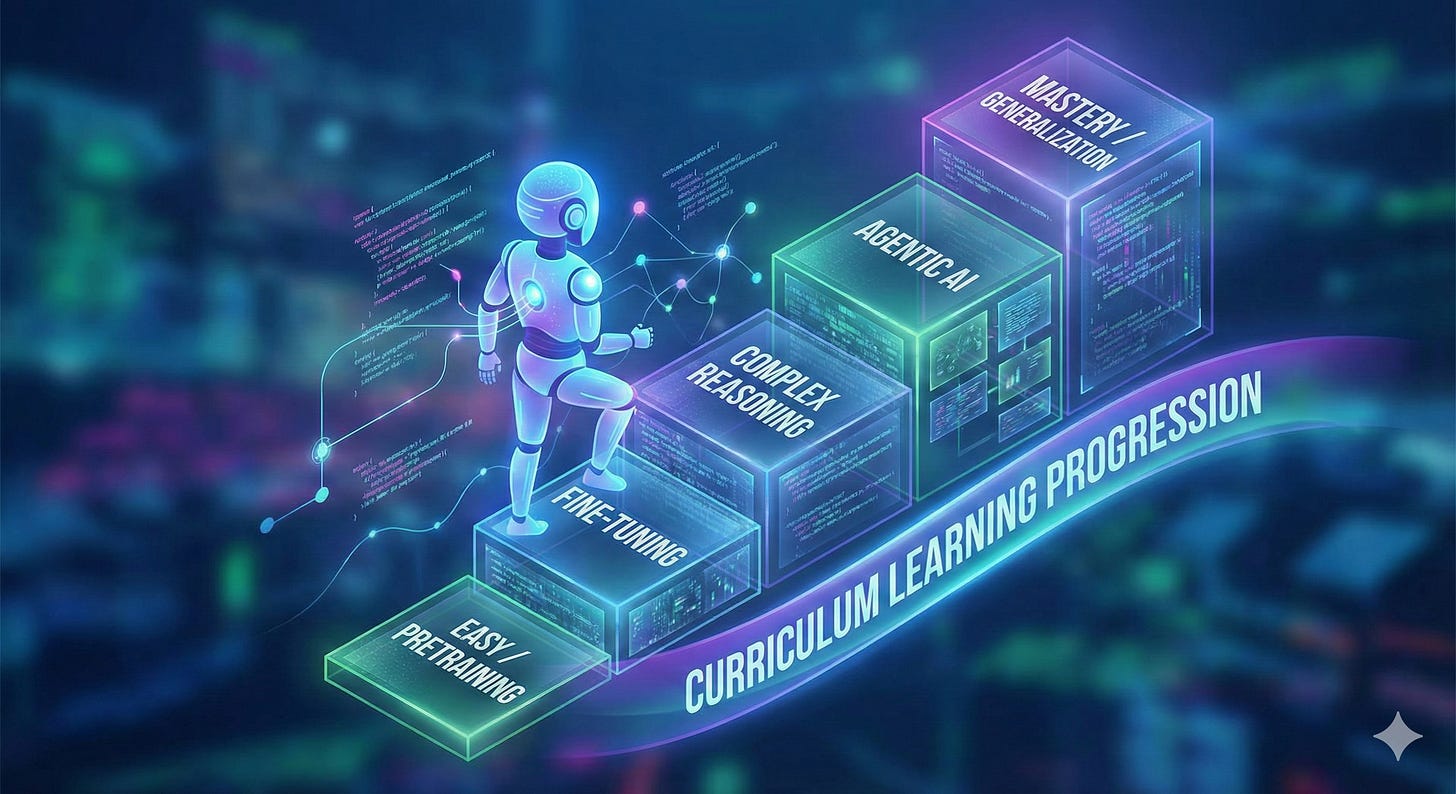

Curriculum learning (CL) is a training strategy in which data or tasks are presented in a structured progression from easier to harder, rather than in random order. The concept, formalized by Bengio et al. (2009), is inspired by human education: learners grasp simple concepts first, then gradually tackle more complex ones. In the context of LLMs, which since 2020 have grown dramatically in size and capability, CL has been explored as a way to improve training efficiency, convergence speed, and in some cases final performance. Traditional LLM training (e.g. GPT-3, PaLM, LLaMA) has generally relied on randomly shuffled data or fixed data mixtures, treating all training samples uniformly. This one-pass, uniform approach has yielded remarkable results in generality CGLS Paper, but it differs from human learning and may not be optimal for developing certain capabilities like long-context reasoning. From 2020 to present, researchers have increasingly investigated curriculum strategies at both the pretraining and fine-tuning stages of LLM development, aiming to mimic human-like learning trajectories or otherwise organize the training process for better outcomes.

In principle, CL for LLMs involves defining a difficulty measure for training examples or tasks, and a schedule or pacing function to introduce more difficult material as the model’s competence grows Beyond Random Sampling Paper. Key expected benefits include faster convergence (fewer training steps or lower compute to reach a given performance) and improved generalization or final performance. Despite these benefits, several studies show that curriculum learning is not universally advantageous. When the difficulty metric is poorly aligned with the model’s actual learning dynamics, curricula can stall convergence or even degrade performance. Recent evaluations in mathematical reasoning (Jia et al., 2025) demonstrate that reverse curricula, beginning with harder examples, sometimes outperform easy-to-hard schedules for more capable models. These mixed findings highlight that CL must be applied carefully, with difficulty signals validated against model behavior rather than assumed a priori. However, applying CL to LLMs presents challenges: What constitutes “easy” vs “hard” data for language modeling? How to quantify task difficulty in a meaningful way? How to schedule progression without destabilizing training? Recent research has addressed these questions through diverse approaches. This report surveys CL approaches for LLM training (2020-2025), with an emphasis on large foundational models (GPT series, PaLM, LLaMA, etc.) and notable insights from other specialized LLMs. We categorize methods by several dimensions of curriculum design: task or data difficulty, sequence length, domain specificity, and data diversity. Both pretraining curricula (ordering of unsupervised training data) and fine-tuning curricula (ordering of supervised tasks or examples) are discussed, along with mathematical formalisms where applicable.

Curriculum Learning in LLM Pretraining

In pretraining (unsupervised learning on large text corpora), curriculum strategies usually focus on organizing the enormous training data by some notion of complexity. Since LLM pretraining datasets can exceed hundreds of billions of tokens, one straightforward curriculum is by text difficulty metrics. Multiple studies (2021–2024) have proposed to rank or cluster text samples from “easy” to “hard” based on measurable features, then train the model on easier texts first. For example, Nagatsuka et al. (2021) increased the input sequence length gradually during BERT pretraining, hypothesizing that short, simple texts are easier for the model to learn than long ones Pre-training a BERT with Curriculum Learning Paper. Their block-size curriculum (starting with shorter text segments and progressively using longer segments) led to faster convergence and better downstream task performance than a baseline with all segments full-length from the start. This demonstrates a sequence length curriculum: effectively controlling the context size difficulty. Longer sequences pose optimization challenges (due to attention complexity and longer-range dependencies), so a gradual increase acts as a curriculum in model capacity to handle context.

In addition, Pouransari et al. (2024) introduced a variable-length curriculum based on dataset decomposition, enabling efficient training of 8k-context models with the compute budget of 2k-context baselines.

Beyond length, researchers have identified many textual difficulty signals. A recent study (Beyond Random Sampling Paper) evaluated six difficulty metrics for LLM pretraining, spanning both linguistic simplicity and information-theoretic measures. These included: readability (e.g. Flesch Reading Ease score), lexical diversity (MTLD measure), information density (compression ratio of the text), syntactic complexity proxies, sequence length (number of tokens), and even model-based surprise (perplexity under a smaller reference model). Formally, one can define a difficulty function D(x) for a training example x; for instance, x’s difficulty might be

or

for compression ratio. Training data is then sorted or partitioned by D(x). The model sees data in order of increasing D(x), rather than a random jumble. The study found that curriculum ordering consistently improved early- and mid-training convergence compared to random shuffling, across all difficulty metrics tested. Notably, some curricula also yielded lasting final gains: when used only as an initial “warmup” phase, an easy-to-hard curriculum still gave up to 3.5% higher end-task performance than a fully random baseline. This suggests that starting with easier texts can lead the model into a better training trajectory or optimum. Among the metrics, compression ratio, lexical diversity, and readability emerged as especially effective difficulty signals (i.e. models trained with these curricula showed the largest improvements). In essence, texts that are less complex in structure or content (shorter, more predictable, more straightforward language) form a foundation before exposing the model to harder, more varied content.

A crucial aspect of curriculum pretraining is the pacing strategy: how fast to move from easy to hard. Rather than a strict one-shot switch from all easy to all hard data, researchers often use pacing functions that gradually shift the sampling mixture. For example, define training progress

A linear pacing might sample mostly from the easiest quantile of data at τ = 0 and linearly increase the difficulty range so that by τ = 1 the model sees the full difficulty range uniformly. A quadratic pacing accelerates the introduction of harder examples later (slow start, then faster increase), whereas an inverse quadratic does the opposite (fast introduction of diverse difficulty, then a slower phase-in of the hardest examples). These schedules can be implemented by partitioning data into difficulty buckets and allocating a fraction of the training budget to each bucket as a function of τ. Alternatively, an interleaved curriculum abandons clear phases and instead mixes difficulty levels at all times, but in a controlled ratio that shifts over time. Empirical results indicate that the best pacing can depend on the metric: for instance, a quadratic schedule worked well with readability and length metrics (quickly ramping up text complexity as the model learns basic syntax), whereas a linear schedule was sufficient for other metrics. Overall, scheduling is an important hyperparameter for curriculum design, analogous to a learning rate schedule for optimization.

Another dimension of curriculum in pretraining is domain and content complexity. Instead of ranking individual samples, one can define easier vs harder data sources or domains. Domain-specific curricula involve training first on a subset of data that is broader or simpler, then gradually incorporating more specialized or challenging domains. More generally, for large general-purpose LLMs, one could imagine first training on a high-quality general corpus and then incrementally adding more niche or complex domains (scientific texts, code, multilingual data, etc.) as a curriculum. Indeed, some large-scale training setups have done mid-training distribution shifts. For example, “mid-training” refers to a coarse two-phase curriculum: recent models like Phi-3 and MiniCPM trained first on generic web data and then in a second phase on higher-quality, more specialized, or longer-form text. This is essentially a quality curriculum, where easy = generic or noisy data and hard = curated or expert data. Such strategies have been reported to yield better zero-shot and reasoning performance than training on the mixed data all at once. The Curriculum-Guided Layer Scaling paper (CGLS, 2024) provides an illustrative case: at 100M parameter scale, they began pretraining on synthetic short stories (simplified content) and later incorporated real web data; at 1.2B scale, they stratified a corpus by technical complexity and proceeded from general texts to highly technical content. In both cases, the models trained with this domain/content curriculum outperformed baselines on knowledge-intensive and reasoning-heavy tasks, confirming that progressively challenging the model with more complex domains improves generalization.

Finally, a novel twist in pretraining curricula is to combine data curriculum with model capacity curriculum. Traditional LLM training uses a fixed network architecture throughout. But one can imagine growing the model as it learns (adding layers or neurons), akin to how human brains develop capacity with age. CGLS (2024) explored this by progressively stacking layers during training in sync with data difficulty. In their setup, the model starts smaller (fewer layers) and new layers are added in stages; each time a layer is added, only the new layer is trained on a more complex data subset while earlier layers are temporarily frozen. Afterwards, the full model is fine-tuned briefly on that data. Then the cycle repeats with an even deeper model and even harder data. This coordinated schedule aligns model capacity with problem difficulty at each stage. Mathematically, if L(k) is the number of layers at stage k and D(k) the data distribution difficulty at stage k, CGLS enforces an increasing sequence L(1) < L(2) <…< L(n) and simultaneously harder data D(1) < D(2) < … < D(n) in terms of complexity. At the 100M-1.3B parameter scale, the results showed that joint curriculum on model and data yields better outcomes than either alone: models trained with CGLS achieved higher zero-shot accuracy on QA benchmarks and better perplexity than training the full model from scratch on all data. For example, a 1.3B-parameter model grown in stages outperformed a baseline 1.3B model by ~1.7% on average across tasks (and up to 5% on an easy QA task) under the same compute budget. This indicates that starting small and simple, then expanding complexity gradually, can be a compute-efficient way to train large models.

Curriculum Learning in Fine-Tuning and Adaptation

After pretraining a base model, a second stage often fine-tunes the model either on specific supervised tasks or via reinforcement learning (e.g. alignment with human preferences). Curriculum learning can be applied at this fine-tuning stage by organizing the sequence of tasks or examples in a deliberate order. Several dimensions of curriculum emerge in fine-tuning: by task difficulty, by input complexity, by domain specialization, and by feedback signals. We discuss each with recent research examples.

Curriculum by Task Difficulty (Supervised Fine-Tuning)

When fine-tuning LLMs on instruction-following or multi-task benchmarks, not all training examples are equal in difficulty. An easy-first schedule can be used, analogous to an educator teaching simple tasks before complex ones. Recent work calls this curriculum instruction tuning Instruction Tuning LLMs with Competence-Aware Curriculum Learning . A basic approach is to design or sort the instruction data by some difficulty heuristic. For instance, Zhao et al. proposed Tree-Instruct, which arranges a collection of instruction-response pairs into a tree where depth corresponds to difficulty; a shallow node might be a simple question, while deeper nodes are more elaborate instructions. The difficulty can be measured by the number of nodes (sub-instructions) in a prompt. Another approach, by Lee et al. (2024), is to generate a curriculum of instructions using a teacher model (like ChatGPT) such that the set is explicitly partitioned into increasing difficulty levels. Their synthesized dataset (named CORGI) contains tiers of instructions from easy to hard, and the target model is trained sequentially on those tiers. These static curricula have shown preliminary effectiveness: models fine-tuned with an easy-to-hard progression of instructions reach higher performance (e.g. better zero-shot generalization or benchmark scores) than those trained on the same data shuffled. Complementary results from Kim & Lee (2024) demonstrate that ordering instructions by attention entropy or prompt length yields additional, although modest, improvements over random shuffling. The intuition is that simpler instructions (like single-step queries or straightforward tasks) help the model solidify its base ability to follow prompts and produce coherent answers. Then, as the fine-tuning data introduces more complex instructions (longer inputs, multi-step reasoning queries, ambiguous tasks, etc.), the model is better prepared to learn from them, rather than being overwhelmed early on.

However, a challenge in curriculum-based fine-tuning is that a static difficulty ranking might not suit all models or remain optimal throughout training. A task that is “hard” initially might become “easy” for the model after some training. This motivates dynamic or competence-aware curricula. Li et al. (2025) address this with the CAMPUS framework (Competence-Aware Multi-Perspective Curriculum for instruction tuning). Instead of fixing the order by a predefined metric, CAMPUS continually adjusts which data the model sees next based on the model’s current performance (competence). In effect, as the model improves, the curriculum scheduler picks more challenging examples, but if the model struggles, it might revert to simpler ones, ensuring an optimal learning trajectory for the current competence level. This is akin to self-paced learning, where the model “chooses” the pace at which difficulty increases. Technically, one can formalize this as optimizing a curriculum policy

that selects the next chunk of data c given the model’s parameters θ_t at time t, so that the loss is minimized while keeping the model’s accuracy on new examples above a threshold. Implementations use techniques like bandit algorithms or adaptive weighting of samples. The benefit of a dynamic curriculum was demonstrated by CAMPUS: it achieved higher final performance on instruction-following benchmarks compared to static curricula and other baselines. In summary, curriculum by task difficulty in supervised fine-tuning can be static (using heuristic difficulty measures like prompt length, number of reasoning steps, etc.) or dynamic (model-guided). Both aim to ensure the model is always training on the most informative examples for its current skill level, avoiding wasted time on trivial examples or, conversely, on examples that are too confusing early on.

Example: Difficulty Metrics for Reasoning: A noteworthy specialization of task difficulty is in reasoning tasks. LLMs are increasingly fine-tuned to perform multi-step reasoning (e.g. math word problems, logical puzzles, multi-hop QA). Here, a natural difficulty metric is the number of reasoning steps required. Jung & Jung (2025) propose using Depth of Thought (DoT) as a difficulty signal (Using Depth of Thought as a Difficulty Signal for Tuning LLMs). They define DoT(x) for a task x by generating a chain-of-thought using a teacher model and simply counting the steps in the reasoning trace. For example, a simple arithmetic question might have DoT = 1 (one step to get the answer), whereas a complex math problem might involve a chain of 5 logical steps (DoT = 5). A curriculum can then train the student LLM on tasks in order of increasing DoT: one-step inference problems first, then two-step, and so on (“shallow → deep” reasoning). This approach aligns with cognitive principles (learn basic arithmetic before advanced multi-step algebra) and provides an interpretable, quantitative difficulty metric beyond surface features like input length. Preliminary results indicate that a DoT-ordered curriculum outperforms curricula based on mere input length or even those scored by heuristic reward models, at least under equal training budgets. This showcases how task complexity in terms of reasoning depth can serve as a curriculum axis to build LLMs that handle increasingly complex reasoning.

Curriculum in Reinforcement Learning Fine-Tuning (RLHF/RL)

Another important fine-tuning stage for modern LLMs is reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF) or other outcome-based training (such as using rewards for correct reasoning or factuality). These procedures typically treat the fine-tuning data (which might be prompt-response pairs with a quality score, or query-answer pairs for a specific task) uniformly. Yet, there is room for curriculum here as well: one can schedule the introduction of more difficult feedback examples or higher expectations as the model’s policy improves. A recent development is Self-Paced Reinforcement Fine-Tuning (SPaRFT) by Do et al. (2025), SPaRFT. SPaRFT implements a curriculum for RL fine-tuning by combining data reduction and adaptive scheduling: first it clusters the training examples by semantic similarity and difficulty level, then uses a multi-armed bandit algorithm to decide which cluster to sample from at each training step. Intuitively, the bandit will allocate more training time to clusters that the model still struggles with (higher reward for learning from those), while skipping or reducing emphasis on clusters that the model has already mastered (no need to repeatedly train on “easy” queries it already gets right). This self-paced selection means the curriculum is not predetermined but arises from the model’s performance. The researchers demonstrated that SPaRFT could reach comparable or better accuracy than standard RLHF on reasoning benchmarks while using far fewer training samples. Essentially, by not wasting time on trivial or redundant examples, the model makes more progress with less data, a direct payoff of curriculum learning. They also found that both the clustering (ensuring diversity and coverage of different difficulty levels) and the adaptive scheduler were important: ablations without these components saw degraded performance.

Another example in RLHF-style tuning is the idea of adaptive reward thresholds or stages. Ouyang et al. (2022) in the InstructGPT work did not explicitly use curriculum, but later methods like “AdaRFT” (adaptive reinforcement fine-tuning) have been mentioned which filter or order the preference data. For instance, one could start by reinforcing the model on obvious high-quality responses vs low-quality ones (an easy distinction), and later, as the model improves, challenge it with more subtle comparisons or a narrower margin of what constitutes a good response (harder distinctions). This mirrors curriculum by reward difficulty, early training uses a coarse reward signal (only learn very clear preferences) and later a finer signal (learn to discern nuanced improvements). While details vary, the overarching theme is that presenting feedback in increasing difficulty (defined by the complexity of the judgment or the necessary improvement) can make RL-based fine-tuning more sample-efficient and effective. Standard practice of uniform sampling in RLHF ignores that some feedback examples might be too easy (the model already satisfies them) or too hard (the model isn’t ready to learn from them), which is precisely what curriculum learning aims to avoid.

Domain-Specific and Multi-Modal Curricula in Fine-Tuning

While less common than in pretraining, domain curricula can also appear in fine-tuning. For example, if one is adapting a general LLM to a specific domain (say legal or medical), a strategy might be to fine-tune first on a subset of tasks or data that overlap between general and domain (to establish basic alignment in that domain’s style), and then progressively focus on the most domain-specific tasks that require specialized knowledge. This resembles continued pretraining followed by task-specific tuning, but one could frame it as a curriculum if done gradually. The antibody model case discussed earlier(link) is essentially a special fine-tuning curriculum (the base model there could be considered a general AbLM on unpaired sequences, then curriculum fine-tuning introduced paired sequences). The result was that a mixed curriculum approach outperformed a one-shot fine-tuning on the new data. The authors note this prevented overfitting and forgetting, which are key risks when moving to a narrow domain. In multi-modal scenarios (where LLMs interface with images or other data), curricula might involve first fine-tuning on single-modality data or simpler multi-modal tasks, then on more complex integrated tasks. Although our focus is on language, the principle extends: whenever a model is adapted to new capabilities, a curriculum can smooth the transition.

Data Diversity Curriculum

A subtle but important curriculum dimension is data diversity, controlling the variety of data the model sees over time. A model might learn better if it is first exposed to a narrower distribution (lower diversity) to master common patterns, then gradually exposed to more diverse styles, genres, or languages. If diversity is introduced too early, the model might fail to grasp any distribution well, whereas a phased increase could allow it to generalize more robustly. Empirical evidence for this comes from multilingual and multi-domain training experiments. For instance, a coarse curriculum might train on one language at a time, sorted by language similarity or resource size, instead of throwing 100 languages at the model from the start. One could start with a high-resource language (more data, thus easier for the model to see frequent patterns) and then add lower-resource languages (harder, more irregular) later. Some multilingual models implicitly do this by oversampling certain languages early on. Similarly, as mentioned, some recent LLM training regimens use a two-phase data mix: first a simpler or cleaner subset, then the full diverse set (which includes more noise or rare patterns, CGLS. This can be seen as first learning the “common denominators” of language, then learning the tail-end varieties and exceptions. The 2024 data curriculum study also tried an “interleaved” strategy, effectively maintaining diversity throughout but ensuring each mini-batch has a mix of difficulties. Interestingly, interleaved curricula gave mixed results: for some metrics it was beneficial (perhaps preventing the model from over-specializing to easy data early), while for others a phased approach was superior. Managing diversity is thus a balancing act, too little early on can overly restrict the model’s representations, but too much can slow down core learning. The curriculum solution is to incrementally broaden the data distribution, which one can formalize by gradually increasing the entropy of the data source mixture over training time.

Curriculum Learning for Agentic AI Systems

As LLMs evolve from static predictors into autonomous agents capable of planning, tool use, and interaction with external environments, CL acquires new significance. Unlike pure language modeling, where training focuses on next-token prediction, agentic behavior requires competence across sequences of decisions, often in environments governed by external states, delayed rewards, and dynamically changing constraints. These characteristics introduce new axes along which curricula can be constructed.

One natural dimension concerns the breadth of the action space. Early in training, an agent might be exposed only to a small, safe subset of tools or API calls, establishing reliability over foundational behaviors before it is permitted to access more powerful or risk-prone capabilities. As competence grows, the agent may gradually unlock more advanced actions, allowing it to perform increasingly complex operations without overwhelming the learning process or incurring catastrophic failures. This staged introduction of actions forms a curriculum over the agent’s operational vocabulary, shaping its ability to interact safely and effectively with its environment.

A second axis relates to the planning horizon. Many agentic failures arise from compounding errors in long sequences of decisions. A planning-centric curriculum therefore begins with short-horizon tasks requiring only shallow reasoning, and progressively introduces tasks with longer chains of dependencies. This mirrors the Depth-of-Thought approach used in reasoning curricula for LLMs: the agent first learns to succeed on single-step or low-complexity problems, and only later encounters environments that demand multi-step deliberation, tool sequencing, or extended temporal reasoning.

A third dimension is the complexity of the environment itself. Just as robotics commonly relies on progressive exposure, from simplified simulators to more realistic physics, agentic systems can benefit from training first in controlled environments with limited distractors or deterministic transitions, and then gradually operating in environments that are richer, noisier, or more stochastic. This shift from simplified settings to realistic conditions acts as a curriculum that stabilizes early learning while ultimately preparing the agent for deployment in diverse or unpredictable contexts.

Multi-agent settings introduce an additional curricular layer. Coordinated behavior is significantly more challenging than single-agent execution, and exposing a model too early to high-interaction scenarios can lead to instability. A coordination curriculum might therefore begin with simple cooperative dyads, then expand to small teams, and eventually introduce mixed-motive or adversarial interactions. In this progression, the agent acquires the ability to reason about the behavior, intentions, or mistakes of other agents, creating a robust foundation for multi-agent ecosystems.

Finally, safety and reliability considerations naturally lend themselves to a curriculum. An agent can be trained to navigate progressively difficult safety-critical scenarios- first avoiding basic harmful actions, then learning to recover from minor failures, correcting hallucinated tool calls, and ultimately detecting more subtle forms of cognitive drift or inconsistency. Such a curriculum aligns closely with emerging research on guardrails, reflex loops, and cognitive-reliability diagnostics, where the goal is not merely correctness but resilience.

Overall, curriculum learning in agentic AI remains an emerging research area, but early evidence suggests it will become central to the development of stable, capable, and safe autonomous systems. As agents must acquire structured skill hierarchies rather than simply model linguistic patterns, ordered competence progression may prove essential for scaling agentic behavior to complex real-world tasks.

Conclusion and Outlook

From 2020 to 2025, curriculum learning has moved from a niche concept to a promising component in the training of large language models. Both pretraining and fine-tuning stages have seen innovative curriculum-based techniques that organize the learning process along intuitive dimensions: start small (in sequence length, model size, or domain scope), start simple (in linguistic complexity or task difficulty), and then scale up gradually. Research demonstrates tangible benefits: faster convergence (saving compute), better sample efficiency, and sometimes higher end-task performance than uniformly-trained counterparts Beyond Random Sampling. Many curriculum methods also achieve substantial compute savings: SPaRFT reduces sample usage by up to two orders of magnitude during RLHF, while sequence-length curricula such as Pouransari et al. (2024) enable long-context training without incurring quadratic attention costs. As summarized earlier, empirical studies confirm measurable improvements in both convergence speed and task performance. These gains are non-trivial given the enormous costs of training LLMs, indicating that curriculum learning could play a key role in the next generation of efficient AI training paradigms.

However, the findings also underscore that one size does not fit all. The optimal curriculum strategy depends on the model size, the data characteristics, and the target tasks. Difficulty metrics must be chosen carefully (e.g. lexical diversity vs. perplexity can target different aspects of “easy”), and static curricula may fall short if the model’s competence rapidly changes. Thus, there is a trend toward adaptive curricula, those that respond to the model (like CAMPUS or SPaRFT) so that the training schedule itself becomes a learned or optimized component of the process. This closes the loop between model and data: the model’s progress dictates what it learns next, an idea very much in line with human tutoring systems.

In conclusion, curriculum learning for LLMs is an exciting fusion of machine learning and educational principles. As we continue to push LLM capabilities (e.g. better reasoning, longer context handling, more specialized expertise), curricula offer a systematic way to inject guidance into the training pipeline. We expect future large-scale models to increasingly report the use of curriculum techniques(difficulty-aware data sampling, multi-stage training phases, or self-paced fine-tuning). The period 2020–2025 has laid the groundwork by verifying on various fronts (from BERT-size models to billion-parameter LLMs) that “learning in order” can indeed make learning better(CGLS). The challenge ahead lies in scaling these methods gracefully and understanding theoretical underpinnings (e.g. why certain curricula yield better minima). Nevertheless, the trajectory is clear: curriculum learning is evolving from an intriguing option to a practical necessity for training ever more capable and aligned language models.

Sources:

Anonymous (2024). Beyond Random Sampling: Efficient Language Model Pretraining via Curriculum Learning, https://openreview.net/pdf?id=p9TKezSBK9. (First systematic study of curricula in LLM pretraining, showing improved convergence and up to 3.5% performance gain with difficulty-based data ordering.)

Nagatsuka et al. (2021). Pre-training a BERT with Curriculum Learning by Increasing Block-Size of Input Text, https://aclanthology.org/2021.ranlp-1.112.pdf. (Introduced sequence-length curriculum; shorter texts first led to faster convergence and better downstream results.)

Do et al. (2025). SPaRFT: Self-Paced Reinforcement Fine-Tuning for LLM, https://arxiv.org/abs/2508.05015v1. (Applied curriculum in RLHF via clustering and bandit scheduling; achieved similar accuracy with fewer samples by adaptively focusing on harder examples as training progresses.)

Dubey et al. (2024). Curriculum-Guided Layer Scaling for Language Model Pretraining, https://arxiv.org/abs/2506.11389v2. (Combined model growth with data curriculum; demonstrated that gradually increasing model depth and data difficulty in tandem improves generalization on reasoning tasks.)

Burbach & Briney (2025). A curriculum learning approach to training antibody language models, Paper link, (Domain-specific curriculum from unpaired to paired antibody sequences; improved performance and avoided catastrophic forgetting compared to fine-tuning.)

Li et al. (2025). Teaching According to Talents: Instruction Tuning LLMs with Competence-Aware Curriculum (CAMPUS), https://arxiv.org/abs/2509.13790v2. (Dynamic curriculum for instruction fine-tuning; adjusts difficulty based on model’s evolving competence, yielding superior instruction-following performance.)

Jung & Jung (2025). Reasoning Steps as Curriculum: Depth of Thought as a Difficulty Signal, https://arxiv.org/abs/2508.18279. (Proposes using the length of chain-of-thought required as a measure of task difficulty for curriculum scheduling in reasoning-heavy fine-tuning.)

Schoenegger et al. (2025). Influence-Based Curriculum Learning for Language Modeling. https://aclanthology.org/2025.babylm-main.26. (Uses influence functions to estimate per-example difficulty; demonstrates large gains for low-resource language modeling by ranking samples by influence.)

Pouransari et al. (2024). Dataset Decomposition: Faster LLM Training with Variable Sequence Length Curriculum. NIPS. (Apple’s long-context curriculum: trains 8k-context models with the compute of 2k; uses buckets of natural sequence lengths.)

Kim & Lee (2024). Strategic Data Ordering: Enhancing Large Language Model Performance Through Curriculum Learning. https://arxiv.org/abs/2405.07490 (Shows modest but consistent gains when ordering instruction data by attention entropy, prompt length, or loss.)